|

|

||

|

Pro Tools

FILMFESTIVALS | 24/7 world wide coverageWelcome ! Enjoy the best of both worlds: Film & Festival News, exploring the best of the film festivals community. Launched in 1995, relentlessly connecting films to festivals, documenting and promoting festivals worldwide. Sorry for the disruptions we are working on the platform as of today. For collaboration, editorial contributions, or publicity, please send us an email here. User loginActive Members |

Laura BlumLaura is a festival correspondent covering films and the festival circuit for filmfestivals.com. She also publishes on Thalo

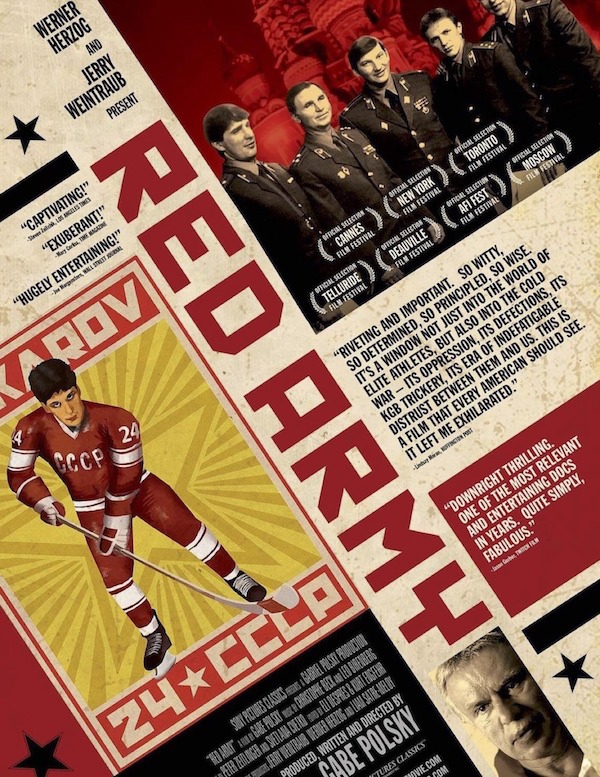

Director Gabe Polsky Talks Hockey Documentary "Red Army"

Gabe Polsky's Red Army is a winning addition to the scorecard of sports-themed films -- like Moneyball and Foxcatcher -- for people who don't give a whit about sports. With dramatic flair and insightful heft, the documentary digs into Soviet social history through the prism of its triumphant national ice hockey team from the height of the Cold War to the unravelling of the USSR. The star of that team and of Polsky's film, Viacheslav "Slava" Fetisov, became the youngest captain in the annals of Soviet hockey. He was primus inter pares of a close-knit brotherhood of players known as the Russian Five -- Sergei Marakov, Igor Larionov, Vladimir Krutov and Alexei Kasatonov -- whose collectivist game strategies were meant to boast Communist prowess. "In the Soviet Union everything you did was in service of your fellow countrymen," Polsky told me on a fogbound New York afternoon bordering on the Russian Gothic. "The whole reason for sports, which is all about working together to win, was to spread this ideology and honor the Motherland." Mama Rusia scored a morale boost. From 1954 to 1991 the hockey gods were with the Soviets, not counting their stunning defeat by Team USA at the 1980 Olympics (and less drastically at the 1960 Games). Red Army chronicles sports developments in step with the era's political machinations, and how these unfolding events affected the lives of the players.

That Polsky came to the story with personal resonances, himself, adds another layer to the proceedings. The son of Ukrainian émigrés who settled in Chicago, he had his own go at Soviet-style hockey when, at age 13, he trained with a coach from the Old Country. He made it to the college league at Yale University, yet defected to filmmaking when realization dawned that he lacked the chops for a professional hockey career. His cinema forays include producing Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans and co-directing with his brother Alan Polsky the indie drama The Motel Life. On January 23, four months after captivating audiences at the New York Film Festival (and following a brief Oscar-qualifying run that inexplicably came to naught), Red Army returns to Manhattan screens for a full commercial release. It was prior to this theatrical opening that Polsky and I sat down to chat. Q: How did the Soviets approach teamwork differently from the Americans? GP: In the Soviet Union it wasn't about who scored the most goals and who's the biggest star, who gets the biggest paycheck. Everyone got the same amount of money and was rewarded for team success, whereas in the West it was completely different. Here you're on a team, but you're rewarded if you score the most goals, or else you're out of there. It's a contradiction.

Q: Given that sports were an extension of warfare and war propaganda, and that the army could draft players to the team, was there anyone who was recruited against their will? GP: There were those who wanted to play for their local team, not for the army. Larry Onoff didn't want to play for the Red Army team, but they drafted him. They said, "Okay, either you play for us or you serve in the army!" Q: If Soviet hockey was propaganda intended to project, "We're better, this is what can happen to a society that functions collectively," was you concerned that by extension you would serve a propagandistic objective? GP: Well, the film was propaganda. Films are propaganda. Any words or images have an effect on people. It's a reflection of ideas. And sports are also communicating ideas to people -- the style of play, the beauty, the aggressiveness -- whatever it is that's being demonstrated. People think about deeper things, like, "Oh man, I wonder what they're doing over there. They play so pretty and it's so interesting; they must be culturally superior." But it's true! And movies show things about our culture, whether about wealth or whatever. Q: What idea did you most want viewers to take away? GP: That this was a creative revolution and that these players were taking the idea of creativity in sport it to another level. That wasn't happening in North America. The way they trained athletes here and the way the athletes played and the way that they thought was not creative. I felt sad about that. Q: The team's two main coaches you feature are creative guru Anatoli Tarasov versus dictatorial KGB appointee Viktor Tikhonov. Is it fair to pull the analogy of Marx and Stalin? GP: That's fair. It's obviously a little bit of an exaggeration, but you can parallel those two. It's an easy way to understand them. Q: Tarasov’s unorthodox coaching strategies were inspired by everything from chess and the Bolshoi Ballet to literature and the circus. Is there a utopian tale here about communism in its purest form -- where it failed as a state regime, the collective ethos was vindicated a credo for physical expression? GP: Yeah, the team realizes the collective ideal. You saw that for the Soviet Union, sport became an art. When you have a philosopher like Tarasov, who can look at things in a different way, then you have the ability to advance sport or anything. Steve Jobs was doing that with computers. Tarasov was smart and creative enough to apply art or ballet or literature or whatever to help make his sport function better and more fun to watch. Q: Where does freedom come in on the ice considering the players' highly disciplined training? GP: It becomes intuitive. They're working as one body. It's not a systematic thing, it's more like jazz, improv. You don't have to play forward, defense, such a confining North American approach. The coaches let them be free on the ice, not off the ice. Q: Is there a particular Russian novel that comes to mind when you reflect on the Soviet team's story? GP: Maybe Crime and Punishment, with the guilt and the contradictions of what's right and wrong. There's a beauty and a tragedy and an insanity like you find with Dostoevsky. It's got these very profound human things that have a lot of heart: the Russian soul. Or nationhood, patriotism, absurdity -- how things work, which Tolstoy talks about in War and Peace. He nailed that balance, and I wanted to have that.

Q: Did you know the documentary was going to be about the rise and fall of the USSR and of the Soviet soul? GP: I really wanted to achieve that from the beginning, because I knew that a hockey documentary, forget it! There's such a small audience for this, and I had to figure out a way to tell a very profound, big story about my heritage and about Russia. Through this team and experience, I had to get to that. I didn't know how it was going to happen, but that's what I had to do. Q: So it was a story of redemption for you too. Was this project a way of cultivating pride in your roots? GP: I dedicated this movie to my parents. For me it's just as much their story as it is Fetisov's. They lived through that. So did a lot of their friends, and my grandparents. I feel like I really got to honor them by telling this story. Growing up, whenever I saw (the Soviet team) play, it made me proud. I was like, "This is my heritage!" But before that I was like, "Eh, whatever, you know, Russia." It just wasn't cool. No one gave a shit here. They said, "They're pussies." But I thought they were astounding. And they dominated. They won. I studied how they played. And I studied the Russian language. I was never interested in filmmaking then, so I had no idea I'd one day make a film about it. Q: Did you approach the game balletically and strategically more like the Soviet team? GP: Yeah, I was more of a creative player, goal scorer, playmaker. That got me into a lot of trouble in the North America system of coaching. I was seen as a rebellious guy who was always doing his own thing. It wasn't fun playing the North American style of playing. Q: How did you make the switch to filmmaking? GP: I thought I could be an NFL player -- and be a good one -- but it was out of my control so I had to find another passion. It was heartbreaking. But my college roommate was doing comedy and writing and I thought it looked interesting. So that's what got me started.

Q: Fetisov flips you the bird at the beginning of the film. How did you gain his confidence and win the Cold War with him? GP: I don't think I ever fully gained his confidence. But he opened up and kept going. I think he felt like I was prepared and that I was going for something interesting even if he didn't really understand what that was. We did three sessions. I never felt that he was fully supportive. Q: What most compelled you about him as a personality? GP: First of all, his story is amazing from a plot standpoint. But he's a complicated, interesting guy to watch. It's not like you've seen this guy before. He's combattive and not afraid to face some crazy stuff. For some reason he felt like he could be more aggressive with me. Q: What hockey roles would you say you guys played in making the film? GP: He was playing defense and I was more of a forward trying to get around him. Q: What guided your filmmaking aesthetic? GP: I tried to develop a style that was classic but different. I didn't want it to be one of these TV sports documentaries with no sense of composition. I wanted it to feel cinematic in the way the frame was shot anamorphically (with a RED camera), but without a sharp digital look. It was important that the locations also give it the feeling of the characters. I didn't want to distract the viewer and be too MTV and cool and hip, but rather to create more of a timeless piece that you could put on 20 years from now and say: that's a great story, visually engaging and compelling. 20.01.2015 | Laura Blum's blog Cat. : Cold War Documentary Gabe Polsky Red Army Slava Fetisov Soviet hockey the Russian Five Independent

|

LinksThe Bulletin Board > The Bulletin Board Blog Following News Interview with EFM (Berlin) Director

Interview with IFTA Chairman (AFM)

Interview with Cannes Marche du Film Director

Filmfestivals.com dailies live coverage from > Live from India

Useful links for the indies: > Big files transfer

+ SUBSCRIBE to the weekly Newsletter DealsUser imagesAbout Laura BlumThe EditorUser contributions |